Exploring the world of art, history, science and literature. Through Religion

Welcome to TreasureQuest!

Look through the treasures and answer the questions. You’ll collect jewels and for each level reached, earn certificates.

How far will you go?

You need an adult’s permission to join. Or play the game without joining, but you’ll not be able to save your progress.

Are there links to current religious practices or a modern equivalent?

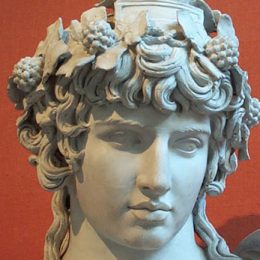

Statues are often made of famous people to celebrate them during or after their life. Antinous was a form of celebrity, famous because he was associated with the Emperor but not because of his own achievements or power.

Where is it from, where is it now?

Websites

Museum of Classical Archaeology Database

Explore the University of Cambridge collections.

The British Museum

The life and legacy of Hadrian

The Independent

Article on a new exhibition looking at the life of Hadrian. Publius Aelius Traianus Hadrianus was not only a peacemaker who pulled his soldiers out of modern-day Iraq, he was also the first leader of Rome to make it clear that he was gay.

The Roman Baths, Bath

Find out more about some of the most important objects in the Roman Baths collection.

Faculty of Divinity

Faculty of Divinity