Exploring the world of art, history, science and literature. Through Religion

Welcome to TreasureQuest!

Look through the treasures and answer the questions. You’ll collect jewels and for each level reached, earn certificates.

How far will you go?

You need an adult’s permission to join. Or play the game without joining, but you’ll not be able to save your progress.

Are there links to current religious practices or a modern equivalent?

It is a portable multifunctional computer – so the closest modern equivalent is probably a smartphone. Like a smartphone, it had lots of clever functions in a small package. It’s also clearly linked to the qibla compass many Muslims use today

Where is it from, where is it now?

Interactive

Interactive Demo

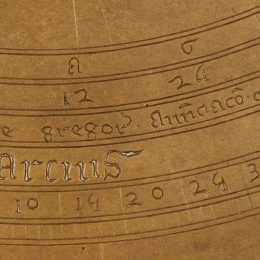

The visualization explains the working and background of the planispheric astrolabe and allows users to experiment with it by adjusting rete and index.

Websites

Astrolabes website

This page provides a very brief definition of planispheric astrolabe principles.

Build Your Own Astrolabe

Excellent information on Astrolabes, including instructions for building (and using) your own!

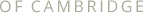

Whipple Museum: A 14th-century English astrolabe

An opportunity to learn more and find out about the different parts of an astrolabe.

Books

Treatise on the Astrolabe

Geoffrey Chaucer

Written for his ten-year-old son, this treatise describes the parts of the astrolabe and things it can be used for.

The History and Practice of Ancient Astronomy

James Evans

1998, OUP

Suitable for advanced GCSE and A’-level students and includes some trigonometry. Provides a thorough background to the subject, with a specific section on astrolabes and instructions on building your own.

God’s Clockmaker: Richard of Wallingford and the Invention of Time

John North

2010, Bloomsbury

Intermediate-advanced book (aimed at a general adult audience), which discusses the religious significance of science.

Faculty of Divinity

Faculty of Divinity