Exploring the world of art, history, science and literature. Through Religion

Welcome to TreasureQuest!

Look through the treasures and answer the questions. You’ll collect jewels and for each level reached, earn certificates.

How far will you go?

You need an adult’s permission to join. Or play the game without joining, but you’ll not be able to save your progress.

Are there links to current religious practices or a modern equivalent?

Lay people still hold meetings outside their places of worship to discuss religious matters and morality, or use internet forums. The closest modern equivalent would most likely be an apologetics groups, [Christian apologetics is a field of Christian theology that presents historical, reasoned, and evidential bases for Christianity, defending it against objections].

Where is it from, where is it now?

Websites

British History Online

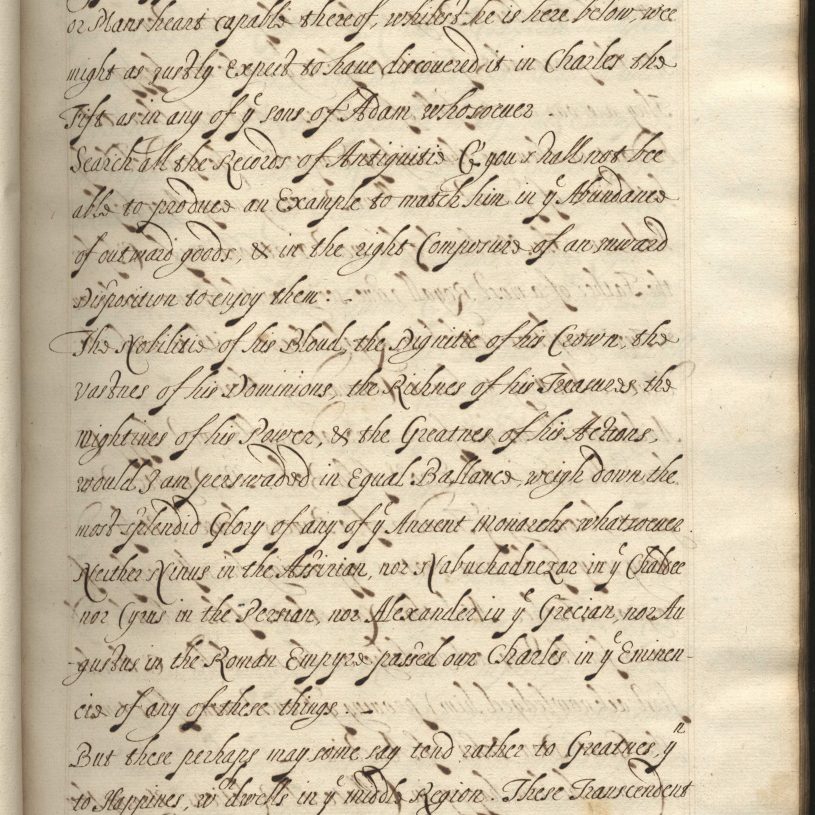

A History of the County of Huntingdon: Volume 1. Appendix: Little Gidding

Bible Research – What is Arminianism?

This site is for students, who are looking for detailed information on the history of the canon, texts, and different versions of scripture.

Videos

Street Wars of Religion: Puritans and Arminians

Professor Wrightson reviews the conflicts which developed within the Church of England in the early seventeenth century and played a role in the growing tensions which led to the English civil wars.

Books

Church and People, 1450-1660 :The Triumph of the Laity in the English Church

Claire Cross

1999, John Wiley & Sons

The Web of Friendship: Nicholas Ferrar and Little Gidding

Joyce Ransome

2011, James Clarke and Co Ltd

Faculty of Divinity

Faculty of Divinity